Criticisms of Israel’s policies of occupation and domination over Palestinian populations in East Jerusalem, the West Bank and Gaza Strip (plus a degree of discrimination against Palestinian citizens of Israel) are almost entirely correct. Where I often differ is when they lack a thorough-going analysis of how this happened, adopting a one-sided viewpoint that portrays Palestinian Arabs and their Arab allies as being entirely without agency historically. For the most part, they downplay or ignore the impact of violence by Palestinian nationalists who have usually targeted Israeli civilians.

Hardline one-staters do not recognize the existence of a Jewish people (solely defining them as a religious group) nor do they acknowledge that the Zionist movement has succeeded in creating an Israeli-Jewish nation as a fact that needs to be reckoned with. To their credit, some one-staters who favor “one democratic state” for Israelis and Palestinians, Jews and Arabs — like Rashid Khalidi and Peter Beinart — do not deny this fact; in other words, they are not advocates of an eliminationist one-state which is basically Arab. But in ignoring the complexities of how we’ve gotten to the current situation of occupation and Israeli-Jewish domination, their one-state advocacy winds up lending support to the eliminationists.

Prof. Rashid Khalidi

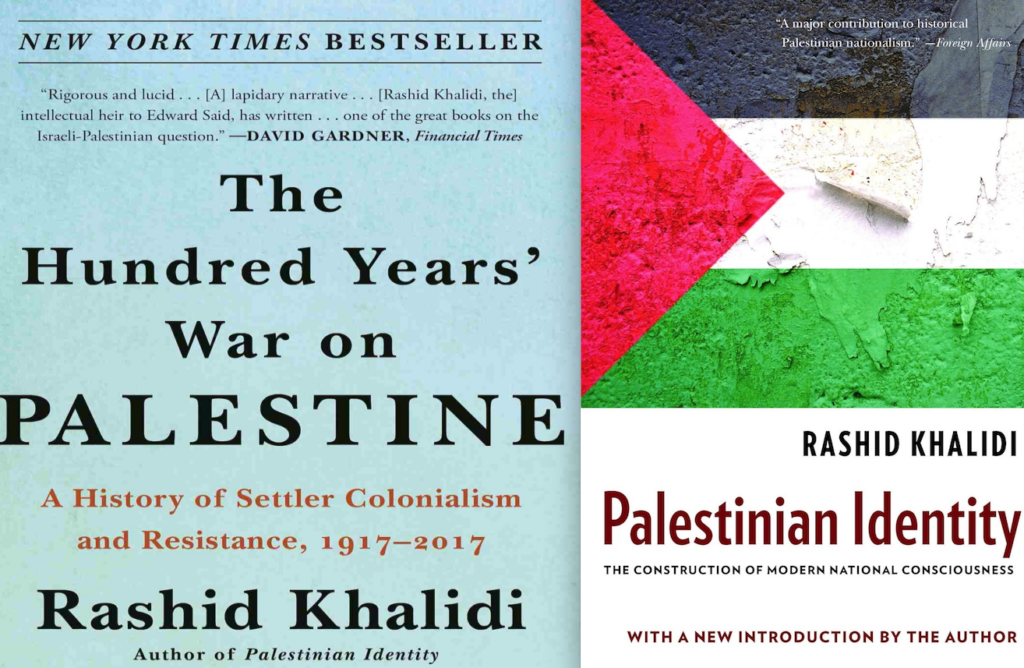

I’ve recently finished reading Khalidi’s 2020 work, The Hundred Years’ War On Palestine. In this and the other book of his that I’ve read, Palestinian Identity: The Construction of Modern National Consciousness, he’s almost entirely one-sided in blaming Zionism for the conflict, but he also acknowledges that Israeli Jews constitute a nation, and that Jews have an ancestral link to the land of Israel/Palestine. This is also the position of Peter Beinart, who in recent years has favored one state over two, identifying himself as a “cultural Zionist” inspired by the example of Ahad Ha’am, who regarded the ancient homeland as a spiritual center for the Jewish people, rather than a likely sovereign Jewish home.

(By way of contrast to Khalidi, Joseph Massad, a fellow history professor at Columbia University, scornfully denies the historic connection of most Jews to the ancient Hebrews and Judeans, regarding this claim as a European invention or myth.)

Prof. Khalidi knows that initially, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) narrowly defined Jews in religious terms and fought their guerrilla/terrorist war with the intention that only Jews with origins in the land before the Balfour Declaration in 1917 (the onset of “Zionist aggression”) would be allowed to remain as citizens of Palestine. He argues, with some justice, that the PLO endorsed a two-state solution for the first time with Arafat’s historic declaration in 1988, opening the door to PLO participation in the Madrid conference and beyond.

Born and raised in New York City in 1948, Khalidi comes from a family with distinguished Palestinian roots, including a former mayor of Jerusalem. He, his wife and children all survived bombardment and privation during Israel’s siege of Beirut in the 1982 war. He was working there as an academic, but as indicated in his 2020 book (largely a memoir), he also had a connection with the PLO. I hate to write this, but my sense is that his scholarly work, although formidable, has been compromised by his outlook as an activist for the Palestinian national cause.

In the early 1990s, during the hopeful years of the Oslo Peace Process — prior to Prime Minister Rabin’s assassination and Bibi Netanyahu’s first electoral victory in 1996, following a wave of suicide bombings — Khalidi participated in public forums organized by Americans for Peace Now (now the New Jewish Narrative). Then he withdrew his support for Oslo; I recall him hoping for a “better peace process,” as if there was a realistic alternative.

He’s long been a critic from the inside of Palestinian nationalist endeavors and attitudes, but in his recent interview on The New Yorker Radio Hour, he barely acknowledged the efforts of Prime Ministers Barak and Olmert to move forward. To The New Yorker’s credit, this same public radio broadcast/podcast also features Adam Kirsch’s critique of the Zionism = Settler Colonialism position.

I’m sorry that Kirsch and Khalidi, two earnest and well-meaning liberal intellectuals, were not recorded together in a conversation. Despite my disappointment with Prof. Khalidi’s views, I understand his legitimate anguish over the ongoing suffering of his people, and hope against hope that they and the people of Israel will somehow emerge from their mutual horrors — as it is said in prayer, speedily in our days.

Two States Are (Still) Better than One

My conclusion remains that two states (or at least a confederation of two states) still makes the most sense, primarily because one unitary state binding two peoples who have engaged in a hundred years’ war is not likely to work. These two peoples couldn’t come to such an agreement in the pre-state Palestine Mandate period; there’s no reason, after all this bloodshed, and especially after Oct. 7th and its bloody aftermath, to believe a peaceful one-state resolution could ever happen. A two-state solution of some sort is the only one that’s come to the threshold of success (e.g., in 2000 and in 2008), and that for most of the 1990s and well into the 2000s commanded majority support among both Israeli Jews and Palestinian Arabs.

Ralph Seliger