The Zionist movement was launched officially in 1897 to attempt to free Jews from persecution by resettling them in the Biblical Jewish homeland. It’s a tragic irony that the country established by this movement over 75 years ago as a bastion against antisemitism has became a trigger for recurring waves of physical and political attacks on Jews around the world.

Déjà Vu All Over Again

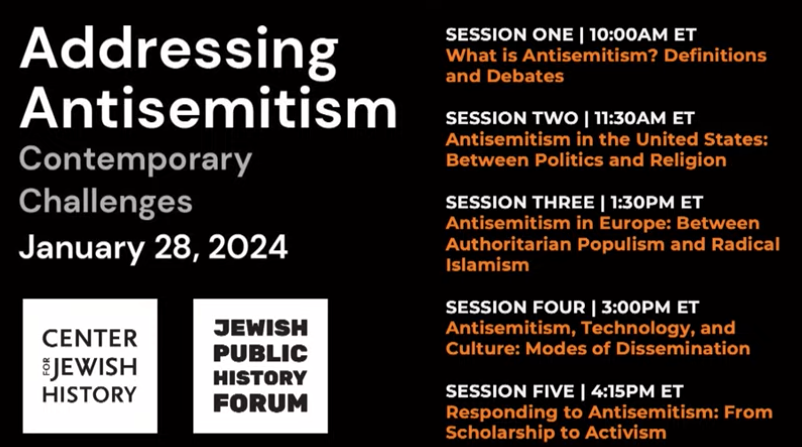

On Jan. 28th, the Center for Jewish History in New York hosted a conference “Addressing Antisemitism.” In May 2003, a stellar gathering of scholars spoke at the same venue on basically the same theme, “Old Demons, New Debates: Anti-Semitism in the West.”

Both events were prompted by global eruptions of antisemitism in response to periods of intense violence between Israelis and Palestinians. Then it was the Second Intifada; now it’s the incredible bloodletting in and near Gaza, with violent repercussions across much of the Middle East.

I wrote a brisk critique in The Forward in 2003, inspiring a letter-to-the-editor accusing me of “blaming antisemitism’s victims.” What drew this ire was my contention that if the Oslo peace process had succeeded, we would not have seen such manifestations of overt antisemitism. More galling perhaps, was my questioning the hallowed dictum that antisemitism is never about what Jews do; I argued that “masses of people … react to news events and visual images,” as happened when losses inflicted by Israeli military action (and sometimes exaggerated) became known during the Second Intifada. Those visuals created embers of hatred in some who didn’t feel it before, and fueled the fire within die-hard haters of Jews. But I was providing an explanation, not justifying antisemitism in any way.

So antisemitic animus is sometimes triggered by what Jews do, or at least are seen as doing. This often emanates from the recurring policies of Israel to expand Jewish settlements and deprive Palestinian Arabs of property and civil rights in territories that would likely be part of a Palestinian state in a peace agreement.

It should be remembered that the actions of Jews like Baruch Goldstein (the 1994 murderer of 29 Palestinians at prayer in Hebron) and the assassin of Yitzhak Rabin played their ugly parts — along with Hamas and other Palestinian terrorists — to derail a potential peace agreement. This history is complicated, but my point was and remains not to simply wring our hands as people at the 2003 conference seemed to be doing. If — in good faith — we learn more about the conflict and the history of Zionist Jews contra Palestinian Arabs and vice versa, we should be in a better position to advocate a peaceful resolution that provides for the security and legitimate rights of both peoples.

Derek Penslar’s Shadow

The recent New York event came off as more conversational and less rhetorical than what transpired at the same location two decades before. Still, the first session (on defining antisemitism) was impacted by an academic brouhaha much closer to hand than the physical crisis in the Middle East, forcing a change in the panel. Derek Penslar, a Harvard professor of Jewish history, has suddenly become a figure of controversy. He withdrew from the conference to forestall any discussion that could compromise his designated role as co-chair of a task force investigating allegations of antisemitism at Harvard.

Penslar’s under attack by some in the Jewish community for signing onto a statement last summer that refers to the occupation (but not Israel proper) as “a regime of apartheid” and for some other references, apparently cherry-picked from Penslar’s latest book, “Zionism: An Emotional State.” Penslar’s replacement on the first panel, Prof. Glenn Dynner of Fairfield University, saluted his work and remarked on the “chilling effect” of “somebody’s arguments and words suddenly being used against them, often twisted and used for a certain agenda.” Others on that panel also indicated their respect for Penslar.

As one of six historians analyzing “the Arab-Jewish conflict in Palestine from 1920 to 1948” for the NY Times Magazine, Penslar illustrated how he’s intellectually honest but not anti-Israel, let alone biased against the interests of Jewish students and scholars. For example, he countered the “narrative” of one of the Palestinians in the discussion that Israel’s victory in 1948 was “inevitable” or even easy.

The Problematics of Polemic and Panic

The misguided assault on Prof. Penslar is reminiscent of a controversial polemic entitled “Progressive Jewish Thought and the New Antisemitism,” a 30-page pamphlet published by the American Jewish Committee in 2006. It blitzed through a torrent of works and individuals critical of Israeli policies — e.g., Jimmy Carter, Tony Judt, Tony Kushner, Adrienne Rich — as being antisemitic in some sense.

Although I am also critical of many of the individuals named in this derogatory way, I share some of their criticisms of Israeli behavior. My feeling about the essay was that the author, Prof. Alvin H. Rosenfeld of Indiana University, was going too far in seeming to regard all liberal criticisms of Israel (even when arguably unfair) as being morally illegitimate.

Today, Prof. Rosenfeld is an emeritus professor at Indiana University and the founder of its Institute for the Study of Contemporary Antisemitism — a partner with the Center for Jewish History in organizing this conference. He moderated the final session, “Responding to Antisemitism: from Scholarship to Activism,” the only one of the five that I found troubling.

Two of the four panelists, Yehudit Barsky (an anti-terrorism expert associated with the Institute for the Study of Global Antisemitism and Policy) and Tammi Rossman-Benjamin (a founder of the university-focused anti-BDS AMCHA Initiative) seemed especially strident in full-on panic mode. Barsky characterized anti-Israel protests as “specifically calling for the genocide of Jews in the streets of this country.” She also claimed “a correlation of funding by Qatar and the rise of antisemitism on elite American campuses,” ignoring a fundamental principle of statistical analysis that “correlation” does not prove causation.

Although anti-Israel activism often crosses into Jew-hatred (or hatred of all things Israeli — its own form of bigotry), this cannot be countered successfully by ignoring either the injustices of the occupation or the humanitarian catastrophe unfolding in Gaza — even acknowledging (as I do) Israel’s right to defend itself. At the same time, we should not deny Palestinians their agency to produce bad actors and actions of their own, as pro-Palestinian activists often do. It’s been noted more than once over the years (and again in this conference) that the best of one side should not be compared with the worst of the other.

Ralph Seliger